By the time the Romans were well established in the north of England, there must have been a definite type of dark colored pony, standing perhaps just over thirteen hands, bred within the local catchment area of Hadrian’s Wall. Bred from visiting stallions and indigenous pony mares, the resulting progeny inherited the strength of a soldier’s mount along with the hardiness, thriftiness and pony character of the north country ponies. Most of the ponies were black, dark brown or bay, and white markings were very rare. As the size of the pony was governed by the quality of grazing, it is unlikely that ponies exceeding 13HH could have survived on the northern moorland.

By the time the Romans were well established in the north of England, there must have been a definite type of dark colored pony, standing perhaps just over thirteen hands, bred within the local catchment area of Hadrian’s Wall. Bred from visiting stallions and indigenous pony mares, the resulting progeny inherited the strength of a soldier’s mount along with the hardiness, thriftiness and pony character of the north country ponies. Most of the ponies were black, dark brown or bay, and white markings were very rare. As the size of the pony was governed by the quality of grazing, it is unlikely that ponies exceeding 13HH could have survived on the northern moorland.

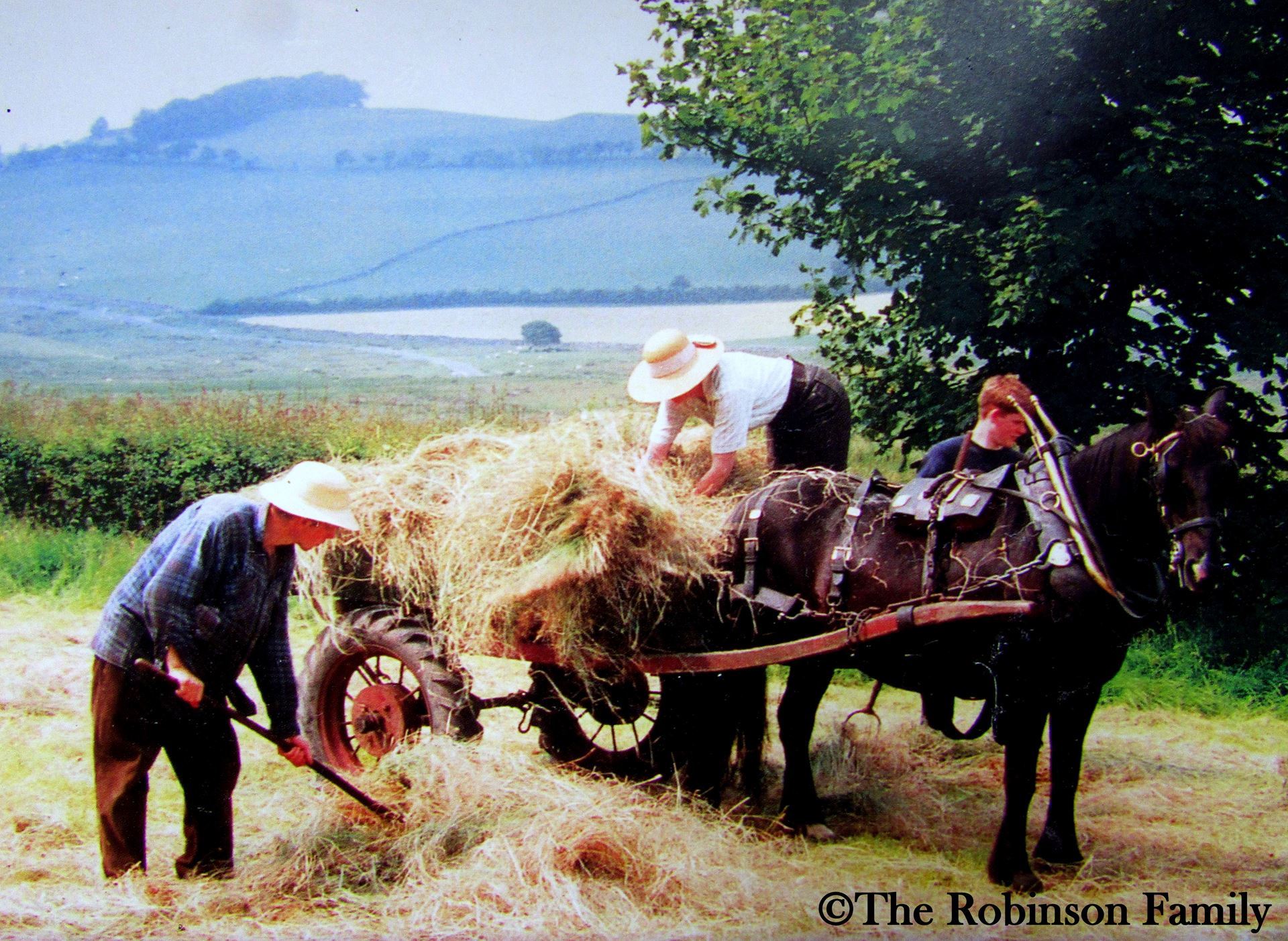

The early Fell Pony type made an ideal working pony. It was strong and sure-footed, placid in nature and not too big to make loading and unloading difficult, while still being up to the weight of a full load. Unlike the small native ponies of pre-Roman times, the improved Fell type was large enough for a man to ride and was recognized as a dual-purpose breed.

The Vikings used the ponies for plowing and sledge pulling, and the Normans for shepherding. By the thirteenth century there was a brisk trade in wool to Belgium, and local ponies were used to transport merchandise around the country. Old packways can still be seen today.

The advent of the Industrial Revolution was a comparatively rapid innovation but one that, directly or otherwise, affected the whole country. Its initial effect on the Fell Pony came by way of iron ore mines situated in the northwest of England. Once excavated, the ore had to be transported across country to the smelting works on the northeast coast, and because of the uneven topography of the country and complete lack of suitable roads and canals, other feasible methods of transport had to be found. The coming of the railways meant redundancy for many of the pony teams and their dependent tradesmen. Within an incredibly short period of time, hundreds of ponies disappeared, many being sold abroad for slaughter. Fortunately, the Fell Pony was still surviving in it’s native Lakeland home, and despite it’s dramatic rise and fall at the hands of the industrialists, as a breed it was quite unchanged, for the disbanding of pony teams had not affected the true pony breeding stock at home on the Cumbrian hills.

The affluent 1950’s saw the beginnings of the popularity of riding for pleasure, a pursuit that has gained momentum ever since and in its wake guaranteed the future of many native breeds. The number of ponies being registered with the Fell Pony Society has risen gradually ever since.

Reference: Clive Richardson, The Fell Pony, J.A. Allen & Company Limited, London.